ABOUT THE BOOK

Ouk Ket in formal attire during the early 1970s, taken probably during his job as third secretary at the Cambodian embassy in Senegal, West Africa. (Image courtesy of Neary Ouk)

Martine (left) and her daughter Neary flying to Cambodia to attend the start of Comrade Duch’s trial in 2009. (Image courtesy of Neary Ouk)

Neary testifies at the trial of S-21’s Comrade Duch in August 2009. (Image courtesy of ECCC)

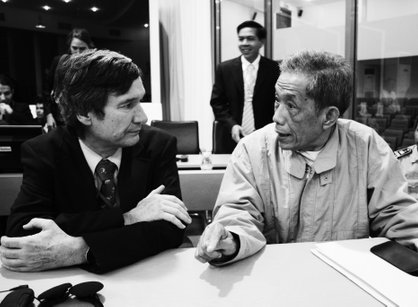

Duch (right) confers with his French defence lawyer François Roux in January 2009. (Image courtesy of ECCC)

'To keep you is no benefit, to destroy you is no loss.'

In 1977, a young diplomat named Ouk Ket was recalled to Cambodia 'to get educated to better fulfil [his] responsibilities'. Left behind in Paris were his French wife and their two young children; they never saw him again. Through this tragedy, the book explores the infamous S-21 prison, the UN-backed trial of its commander, and Cambodia's years of terror.

During the Khmer Rouge's four-year rule of terror, two million people, or one in every four, Cambodians, died. In describing one family's decades-long quest to learn their husband's and father's fate and the war crimes trial of Comrade Duch (pronounced 'Doyk'), who ran the notorious S-21 prison in Phnom Penh, where thousands were tortured prior to their execution, When the Clouds Fell from the Sky illuminates not only the tragedy of a nation, but also the fundamental limitations of international justice.

In February 2012, the international war crimes court in Cambodia handed down a life sentence to the man known by his revolutionary moniker Comrade Duch. The court found the Khmer Rouge's former security chief responsible for the deaths of more than 12,000 people at S-21 prison. Duch died in September 2020.

Duch's conviction was historic. He was the first Khmer Rouge member to be jailed for crimes committed during Pol Pot's catastrophic 1975-9 rule when two million people died from execution, starvation, illness and overwork as Cambodia underwent the most radical social transformation ever attempted. When the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, the entire population was driven from the towns and cities into rural gulags, where they were put to work planting rice and constructing vast irrigation schemes Designed to outdo even Mao's Great Leap Forward, it was an unparalleled disaster.

At the same time as the Khmer Rouge sought to refashion the country, they closed its borders, barred all communication with the outside world and turned back the clock to Year Zero. They outlawed religion, markets, money, education and even the concept of family as they pursued a revolution that would outstrip all others. In Orwellian fashion, everything and everyone belonged to Angkar, the anonymous leaders, and all loyalty was owed to them. The individual had no value beyond their utility as a working unit that could easily be replaced.

It was not long before the revolution began to implode, driven to destruction by the incompetence and paranoia of Angkar. Yet instead of recognising their own failings, the leaders believed unseen enemies were undermining the revolution. They sought them everywhere, both inside and outside the movement. In their pursuit of purity, they destroyed a nation.

This was the closed nation to which Ouk Ket returned in 1977. Like hundreds of other returnees, he was utterly unaware of the terrors being wrought in the revolution's name. Hundreds of thousands of other Cambodians perished in nearly 200 institutions like S-21 that formed an inescapable web across the country. Most of the rest died of starvation, overwork and illness in the rural gulags.

Cambodia remains defined by this cataclysmic period, and its effects are apparent today. To illustrate this era and its consequences, Robert Carmichael has woven together the stories of five people whose lives intersected to traumatic effect. Duch is one of those five, and the book tackles this complex man and his life through the prism of his trial.

The second person is a Frenchwoman called Neary. Her father - the returning diplomat Ouk Ket - was one of Duch's 12,000 proven victims. She was just two when he disappeared. When the Clouds Fell from the Sky is as much about Neary as it is about Duch: her efforts to find out more about the fate of her father, and her subsequent battle to accept it. Towards the end of the book, in one of its key scenes, Neary testifies against Duch at the international war crimes court in Phnom Penh.

The third and fourth characters are Ket and his wife Martine, who met in 1970 when they were studying at university in Paris. The fifth is Ket's cousin Sady, who never left Cambodia and who worked as a teacher in Phnom Penh after the Khmer Rouge were overthrown in 1979. Sady and Ket grew up together in 1960s' Phnom Penh, so Sady is able to tell us about Ket's early years. She also describes the reality of life under the Khmer Rouge: the forced eviction from Phnom Penh in 1975, the murder of her younger brother in 1977, the deaths of Ket's father and siblings, and her suffering in the rural labour camps. Sady's story is the experience of countless Cambodians.

Through these five stories, through the author's own research, through interviews with leading academics, former Khmer Rouge and ordinary Cambodians, and by following Duch's trial, which Robert did for months, the book takes the experience of one forgotten man to tell the story of a nation.

Since we cannot grasp the concept of millions of dead, he has used the murder of one to speak for the deaths of many. In so doing the book reaffirms the value of the individual, countering the Khmer Rouge's nihilistic maxim that: 'To keep you is no benefit, to destroy you is no loss.'